Are Your Palpitations Due to Benign Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs)?

Almost everybody has PVCs if you monitor their heart rhythm for 24 hours but the vast majority of them do not cause significant problems

The skeptical cardiologist published his manifesto on the major cause of irregular heartbeat in 2017. I updated readers with a description of my own PVCs and how Kardia’s Alivecor aids in identifying them in 2021. (Surprisingly, Apple Watch still cannot identify PVCs.)

What follows is my updated summary on these pesky premature beats.

If you feel your heart flip-flopping, then you are experiencing palpitations: a sensation that the heart is racing, fluttering, pounding, skipping beats or beating irregularly.

Often, this common symptom is due to an abnormal heart rhythm or arrhythmia.

The arrhythmias that cause palpitations range from common and benign to rare and lethal, and since most individuals cannot easily sort out whether they have a dangerous or a benign problem, they often end up getting cardiac testing or cardiology consultation.

The most common cause of palpitations, in my experience, is the premature ventricular contraction, or PVC (less commonly known as the ventricular ectopic beat or VEB).

Premature Ventricular Contractions-Electrical Tissue Gone Rogue

The PVC occurs when the ventricles of the heart (the muscular chambers responsible for pumping blood out to the body) are activated prematurely.

This video explains the normal sequence of electrical and subsequent mechanical activation of the chambers of the heart.

To get an efficient contraction, the electrical signal and contraction begins in the upper chambers, the atria, and then proceeds through special electrical fibers to activate the left and right ventricles.

Sometimes this normal sequence is disrupted because a rogue cell in one of the ventricles becomes electrically activated prior to getting orders from above. In this situation, the electrical signal spreads out from the rogue cell and the ventricles contract out of sequence or prematurely.

This results in a Premature Ventricle Contraction.

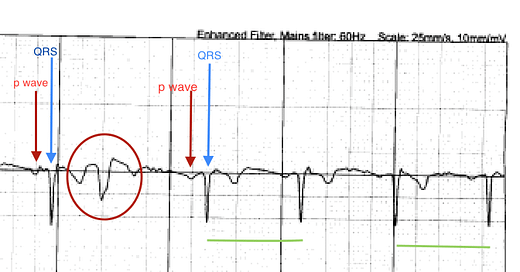

I recorded the above AliveCor tracing in my office on a patient who suffers palpitations due to PVCs (we'll call her Janet).

The wider, earlier beat (circled in red) in the sequence is the PVC. The prematurity (earliness) of the PVC means that the heart has not had the appropriate time to fill up properly.

As a result, the PVC beat pumps very little blood and may not even be felt in the peripheral pulse1. Patients with a lot of PVCs, (for example, occurring every other beat in what is termed a bigeminal pattern), often record an abnormally slow heart rate because only one-half of the heart's contractions are being counted.

While recording this, every time Janet felt one of her typical "flip-flops," we could see that she had a corresponding PVC and the cause of her symptoms was made clear.

There is a pause after the PVC because the normal pacemaker of the heart up in the right atrium (the sinus node) is reset by electrical impulses triggered by the PVC.

The beat after the PVC is more forceful due to a more prolonged time for the ventricles to fill and consequently, most patients feel this pause after the PVC rather than the PVC itself,

PVCs are common and most often benign.

I have patients who have thousands of them in a 24-hour period and feel nothing.

On the other hand, some of my patients suffer disabling palpitations from very infrequent PVCs.

From an electrical or physiologic standpoint, there seems to be neither rhyme nor reason why some patients are exquisitely sensitive to premature beats.

How Do I Know If My PVCs Are Benign?

My patient, Janet, is a great example of how PVCs can present and how inappropriate or inaccurate heart tests done to evaluate PVCs can lead to anxiety and unnecessary and dangerous subsequent testing.

A year ago, Janet began experiencing a sensation of fluttering in her chest that appeared to be random. Her general practitioner noted an irregular pulse and obtained an ECG, which showed PVCS. He ordered two cardiac tests for evaluation of the palpitations: a Holter monitor and a stress echo.

A Holter monitor consists of a device the size of a cell phone connected to two sensors or electrodes that are stuck to the skin of the chest area. (Since 2017, the type of monitor I use almost exclusively is a patch monitor2 which is much less intrusive and can easily be worn for a week or two.)

The electrical activity of the heart is recorded for 24 or 48 hours, and a technician then scans the entire recording looking for arrhythmias while trying to correlate any symptoms the patient recorded with arrhythmias. The monitor allows us to quantitate the PVCs and calculate the total number of PVCs occurring either singly or strung together as couplets (two in a row), or triplets (three in a row.)

Janet's monitor showed that over 24 hours her heart beat around 100,000 times with around 2500 PVCs during the recording. Unfortunately, the report did not mention symptoms, so it was not possible to tell from the Holter if the PVCs were the cause of her palpitations.

A stress echocardiogram combines ultrasound imaging of the heart before and after exercise with a standard treadmill ECG. It is a very reasonable test to order in a patient with palpitations and PVCs, as it allows us to assess for any significant problems with the heart muscle, valves or blood supply and to see if any more dangerous rhythms like ventricular tachycardia occur with exercise. If it is normal, we can state with high certainty that the PVCs are benign.

Benign, in this context, means the patient is not at increased risk of stroke, heart attack, or death due to the PVCs.

In the right hands, a stress echocardiogram is superior to a stress nuclear test for these kinds of assessments for three reasons:

-Reduced rate of false positives (test is called abnormal, but the coronary arteries have no significant blockages)

-No radiation involved (which adds to costs and cancer risk)

-The echocardiogram allows assessment of the entire anatomy of the heart, thus detecting any thickening (hypertrophy), enlargement, or weakness of the heart muscle, which would mean the PVCs are potentially dangerous.

Unfortunately, my patient's stress echo (done at another medical center) was botched and read as showing evidence for a blockage when there was none. This is a false positive result.

As a result an invasive and potentially life-threatening procedure, a cardiac catheterization was recommended.

Similar to the situation I've pointed out with the performance and interpretation of echocardiograms (see here), there is no guarantee that your stress echo will be performed or interpreted by someone who actually knows what they are doing. So, although the stress echo in published studies or in the hands of someone who is truly expert in interpretation, has a low yield of false positives, in clinical practice the situation is not always the same.

Given that Janet was very active without any symptoms, she balked at getting the catheterization and came to me for a second opinion.

I reviewed the stress echo and felt it was a false positive and did not feel the catheterization was warranted.

We discussed alternatives, and because Janet needed more reassurance of the normality of her heart (partially because her father had died suddenly in his sixties) and thus the benignity of her palpitations/PVCs, she underwent a coronary CT angiogram instead.

This noninvasive exam (which involves IV contrast administration, and is different from a coronary calcium scan), showed that her coronary arteries were totally normal.

Benign PVCs-Treatment Options

Once we have demonstrated that the heart is structurally normal, reassurance is often the only treatment that is needed. Now that the patient understands exactly what is going on with the heart and that it is common and not dangerous, they are less likely to become anxious when the PVCs come on.

PVCS can create a vicious cycle because the anxiety they provoke can cause an increase in neurohormonal factors (catecholamines/adrenalin) that may increase heart rate , make the heart beat stronger and increase the frequency of the PVCs.

Some patients, find their PVCs are triggered by caffeine (tea, soda, coffee, chocolate) or stress, and reducing or eliminating those triggers helps greatly. Others, like Janet, have already eliminated caffeine, and are not under significant stress.

PVCs can come and go in a seemingly random fashion.

I discuss treatment options for these patients with benign PVCs who continue to have troubling symptoms after reassurance and caffeine/stress reduction in my post entitled "Treatment of Benign Premature Ventricular Contractions."

(I will update the treatment article soon.)

Prematurely Yours,

-ACP

As a result of this, it is not uncommon for devices that rely on counting the peripheral pulse (like Apple Watch, Fitbit, etc.) to determine heart rate to dramatically underestimate heart rate in patients with PVCs. For example, if every other beat is a PVC in a patient with a heart rate of 80 beats per minute, the wrist-based device would yield a heart rate of 40 beats per minute. I’ve had many patients referred to me for “bradycardia” who had experienced this same phenomenon.

The original patch monitor was the Zio and I feel it revolutionized the field. When I wrote in detail about monitoring devices in Which Ambulatory ECG Monitor For Which Patient? in 2019 I said:

The advantage of the patch monitors is that they are ultraportable, relatively unobtrusive and they monitor continuously with full disclosure.

The patch is applied to the left chest and usually stays there for two weeks (and yes, patients do get to shower during that time) at which time it is mailed back to the company for analysis.

I’m currently using Bardy patch monitors for my outpatient monitoring.

Good article. I think one of the missed items may be what we tried to use in clinical trials for determining what an abnormal amount of PVCs actually are in “otherwise healthy subjects”. We set 2% and 5% cutoffs to determine that more thorough diagnosis is needed when they exceed 5%.

Coming from an ion channel group in pharma that looked to develop the next generation anti-fibrillatory drug, and working for Bristol-Myers Squibb who’s drugs were killed by the CAST and SWORD studies, I can attest that crushing PVCs due to symptoms alone (since we now now that, in isolation, they are largely harmless) is NOT warranted. My personal experience as a lifelong fit pharmacologist is that the autonomic nervous system play an outsized role in many people with frequent, benign PVCs. If I exercise regularly, my PVCs are minimal. When de-conditioned, even after one week, they come back. It’s my proof of the long-held pharmacological principle of ying-yang. We should always consider the autonomic nervous system when evaluating PVC.

As a patient, I just want to pop in to say that the Zio Patch was a game-changer in my diagnostic journey. Prior to its use as a diagnostic tool I had been fitted with 12 and10 lead halter monitors, which are cumbersome, and cannot be worn for much more than a couple of days. In 2017, I was monitored for the first time using the Zio patch and the amount of freedom to do the exercise I normally do, to fully participate and life my life the way I normally would. This supported clear diagnosis in a way that was not possible when you have multiple leads snaking across your body.

As someone with a LBBB, and intermittent PVCs, the Zio is an amazing diagnostic tool. I am still surprised it is not utilized more.