Do the Health Benefits of Cycling Outweigh the Risks?

And should you wear a helmet while riding a bike revisited

After the skeptical cardiologist participated in the 2014 5 Boro NYC bike Tour he began pondering the overall value of cycling as transportation.

Since cycling is physical exercise and there is scientific evidence (observational studies only) linking regular physical activity to a significant cardiovascular risk reduction, we might expect that using a bike rather than sitting in a car to get around would help us live longer.

A reasonable physical activity goal, endorsed by most authorities, is to engage in moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity for a minimum of 30 min on 5 days each week or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity for a minimum of 20 min on 3 days each week.

This level of exercise helps with weight control, improves your cardiorespiratory fitness, and is associated with lower mortality from cardiovascular disease.

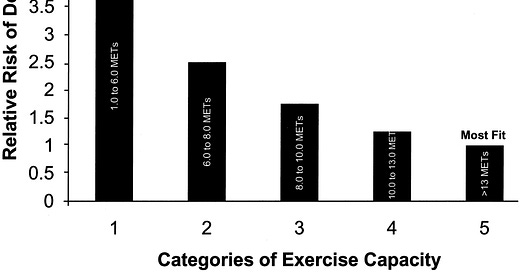

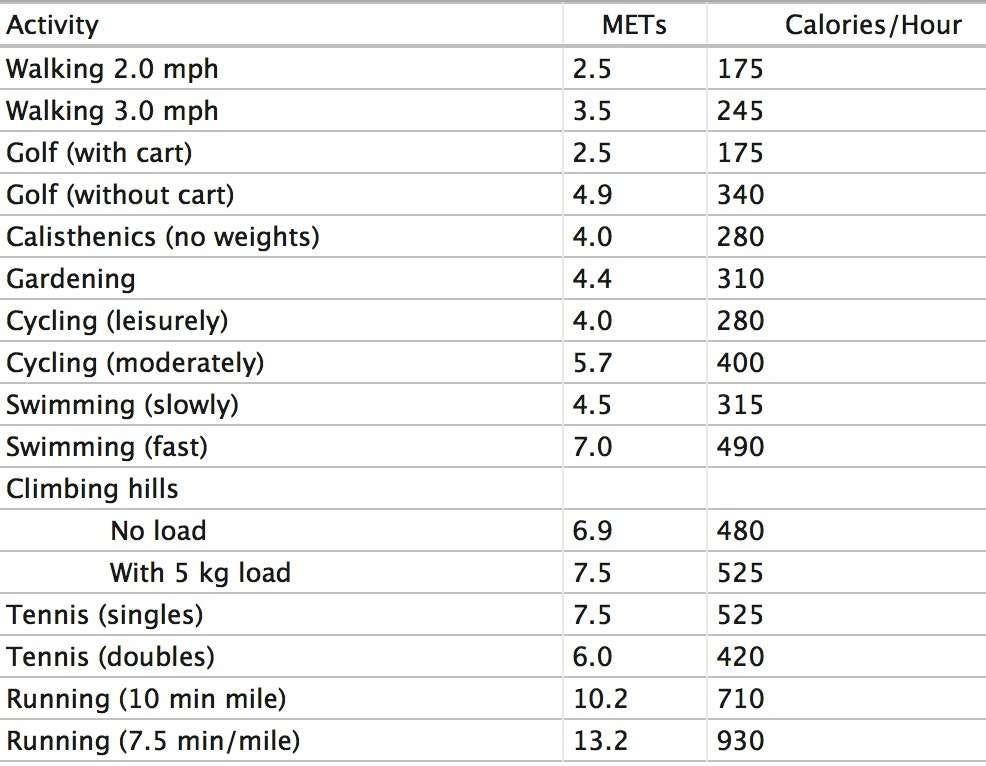

The metabolic equivalent of task (MET) is a measure of the energy cost of physical activity. The chart below gives METs for various activities. Individuals should be aiming for 500–1,000 MET min/week. Leisure cycling or cycling to work (15 km/hr) has a MET value of 4 and is characterized as moderate activity.

A person shifting from car to bicycle for a daily short distance of 7.5 km would meet the minimum recommendation (7.5 km at 15 km/hr = 30 min) for physical activity in 5 days (4 MET × 30 min × 5 days = 600 MET min/week).

Thus, cycling to work for many individuals would provide the daily physical activity that is recommended for cardiovascular benefits. However, cycling in general, and urban cycling in particular, carries a significant risk of trauma and death from accidents and possibly greater exposure to urban pollutants.

Traffic Deaths Driving Cars versus Bicycles in the Netherlands

The table below shows the estimated numbers of traffic deaths per age category per billion passenger kilometers traveled by bicycle and by car (driver and passenger) in the Netherlands for 2008.

These data suggest that there are about 5.5 times more traffic deaths per kilometer traveled by bicycle than by car for all ages. Interestingly, there is no increase in risk for individuals aged 15-30 years.

On the other hand, those of us in the “baby-boomer” generation (?slowed reflexes, poor eyesight, impaired hearing) and older are at an 8 to 17-fold increase risk.

In the Netherlands, where a very large percentage of the population regularly rides bikes, there has been considerable scientific study of the overall health consequences of biking and we have reasonably good data on the question of the relative safety of biking versus driving a car for short distances.

You can watch the happy people of Groningen (“the world’s cycling city”, where 57% of the journeys in the city are made by bicycle) riding their bikes here.

Impact of Transition from Car to Bike for Short Tris

One study quantified the impact on all-cause mortality if 500,000 people made a transition from car to bicycle for short trips on a daily basis in the Netherlands and concluded

For individuals who shift from car to bicycle, we estimated that beneficial effects of increased physical activity are substantially larger (3–14 months gained) than the potential mortality effect of increased inhaled air pollution doses (0.8–40 days lost) and the increase in traffic accidents (5–9 days lost). Societal benefits are even larger because of a modest reduction in air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and traffic accidents.

Apart from the highest average distance cycled per person, the Netherlands is also one of the safest countries in terms of fatal traffic accidents so it's reasonable to ask whether these data apply to other countries. This study concluded

When traffic accident calculations for the United Kingdom were utilized, where the risk of dying per 100 million km for a cyclist is about 2.5 times higher, the overall benefits of cycling were still 7 times larger than the risks.

If you decide to bike to work this week, braving the elements, the possible automobile collisions, and the automobile exhaust you can rest comfortably with the thought that not only are you prolonging your own life but by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution you are contributing to the health of everyone around you.

Bikeridingly Yours,

-ACP

N.B. This is an upgraded version of my post from 2014. Since then I have visited the Netherlands and written about how heart-healthy and happy the Duch are. It is my firm but unsubstantiated belief that bike riding is a strong contributor to those traits.

N.B.2 In 2015 I revealed that I don’t wear a bike helmet when cycling in a post entitled “Is Not Wearing a Bike Helmet As Stupid as Smoking Cigarettes?” I felt the medical literature supported my unhelmeted stance even after a colleague had a horrific accident cycling (Hit and Run Drivers and Bike Helmets.) As of a week ago, however, I joined the ranks of the helmeted.

This dramatic change was not related to a recent article in Neurotrauma but to two more cycling accident anecdotes and a recognition that cycling in Encinitas involves many more car/bike interactions than riding the Great Urban Bike Ride in St. Louis.

Amazing how TSC always findings such topical issues to discuss. I did have a bad accident on the bike on a bike trail which made me nervous and reconsider the adage "there are old bicyclists and there are bold bicyclists but there are no old, bold bicyclists".

So the other comment is more of historic interest. People assume that the Dutch, what with their windmills and tulips and dykes and clogs, have been riding bikes since the Flood.

Quite the opposite, theirs was as car-centric a culture as existed in Europe, until the 1973-74 Arab Oil Embargo, where they were the only country in Europe that didn't cave and stuck with Israel. Instead, (among other fuel-saving measures) they created carless Sundays and it didn't take long for them to figure out that being carless was a great thing and they started turning their transportation culture 180 degrees.